From the idyllic Hawaiian islands, the mesmerizing art form that is the hula dance has captivated hearts worldwide with its lyrical chants (oli) and melodic songs (mele).

So much so that whenever “Hawaii” is mentioned, most people immediately think of dancers in grass skirts and feathered tops.

Truly, this ancient tradition is intertwined with the very fabric of Hawaiian culture.

In this article, we’ll guide you through the captivating world of hula dance, unearthing its origins and guiding you through the various moves performed on stage.

We’ll also look at the dancers’ intricate costumes and what each element of the outfit means. Through it, you’ll be able to take a glean at the heart and soul of the Hawaiian islands!

Table of Contents

What Is Hula Dance?

The Hula dance is a traditional form of expressive dance deeply rooted in the culture and history of the Hawaiian islands.

It serves as a medium for storytelling, preserving legends, myths, and the rich heritage of the Polynesian people who made their home on the Hawaiian islands around the 5th century BC.

The dance movements are accompanied by rhythmic chants (oli) and melodic songs (mele). This creates a harmonious fusion of hula dance music, dance, and storytelling.

Hula dance can be categorized into two main styles: Hula Kahiko and Hula ‘Auana.

- Hula Kahiko, also known as ancient Hula, is the traditional form that’s been practiced by the Hawaiian people for centuries. It incorporates slow, deliberate movements, depicting historical events, gods, and mythical tales.

- Hula ‘Auana, referred to as the modern hula, embraces faster-paced movements, graceful gestures, and Western instruments.

Notably, other than styling and instrumentations, the hula dance is further split into two kinds based on whether the dancers are sitting or standing when performed.

The seated version is called “noho,” while the standing version is “luna.”

Today, hula dance has transcended its cultural boundaries and is enjoyed by people worldwide.

It is performed on various occasions, including festivals, weddings, and cultural events. It serves as a powerful connection to Hawaiian traditions and celebrates the island’s vibrant culture.

Hula Dance Origin & History

Origins

Like most ancient traditions and rites, many legends supposedly tell the mythical origin of the hula dance.

Though there is no “official” version of the story, they all offer fascinating glimpses into the birth of this cherished art form. They all showcase how profoundly connected the Hawaiian culture is.

One legend tells of Laka, the goddess of hula. Laka is said to have given birth to the dance in Kaʻana, a sacred place on the island of Molokaʻi.

Following Laka’s passing, her remains were concealed beneath the hill Puʻu Nana, becoming a sacred site forever tied to the hula dance.

Another tale revolves around Hiʻiaka, who danced to appease her volcanic sister, Pele, the goddess of fire.

According to this story, hula’s source can be traced to the Hāʻena shoreline in the Puna district of Hawaiʻi. This ancient hula, known as Ke Haʻa Ala Puna, immortalizes the event.

Another legend also recounts Pele’s quest for a safe haven away from her sister Namakaokahaʻi, the goddess of the oceans.

Eventually, Pele discovered an island where the waves could not touch her – the island of Hawai’i. There, she performed the inaugural hula dance, symbolizing her triumph.

Kumu Hula (hula master) Leato S. Savini, from the Hawaiian cultural academy Hālau Nā Mamo O Tulipa, believes that the roots of hula extend back to the Kumulipo.

It’s the Hawaiian account of the creation of the world by the god Kane.

Kumu Leato suggests that the movements and chants used by the gods during the creation of Earth, mankind, and womankind formed the very foundation of hula.

These legends intertwine myth, spirituality, and cultural reverence. They add an air of mystique to the origins of hula dance, which continues to enchant and inspire dancers and audiences alike.

Check more: Flamenco Dance: Origin, Costume, Music, Notable Dancers & More

Hula Dance In The 19th Century

In 1820, American Protestant missionaries arrived in Hawaii and castigated the hula dance as a pagan practice tainted by heathenism.

Their influence led to calls for the newly Christianized aliʻi (royalty and nobility) to outlaw the hula.

Queen Kaʻahumanu enforced a ban on public performances in 1830, although some aliʻi supported the hula privately. By the 1850s, a licensing system was implemented to regulate public hula.

However, a revival of Hawaiian performing arts occurred during the reign of King David Kalākaua (1874–1891).

King Kalākaua was a proponent of traditional crafts. And Princess Lili’uokalani played a pivotal role as the patron of ancient chants (mele) and hula.

They sought to rekindle the fading ancestral culture amid the encroaching influences of foreigners and modernism rapidly transforming Hawaii.

During this period, practitioners innovatively merged Hawaiian poetry, vocal performance, dance movements, and costumes to create a new form known as hula kuʻi.

This hybrid style aimed to combine elements of the old dances with the new. Traditionally, the dance is a strictly choreographed affair. But with the new changes, improvisation is introduced to the hula.

The pahu drum, regarded as sacred, was not used in the hula kuʻi. Instead, the ipu – a percussion instrument made from gourds – became closely associated with this dance.

Throughout its evolution, hula remained deeply rooted in ritual and prayer.

Even in the early 20th century, training and practice were imbued with reverence for the goddess of the hula, Laka. Despite efforts to suppress it, the hula dance has persevered and lasted into the modern era.

Hula Dance In The 20th Century

The early 20th century brought significant transformations to the hula dance. Besides finding itself in the world of Hollywood, the hula dance became a tourist staple for the Hawaiian islands.

The Kodak Hula Show and Signe Paterson elevated the visibility and popularity of hula on American stages. The dance is also placed in the repertoire of the Royal Hawaiian Orchestra.

However, amidst these mainstream developments, a more traditional form of hula persisted in smaller circles maintained by elderly practitioners.

In the 1970s, a resurgence of interest in hula emerged with the Hawaiian Renaissance. This cultural movement renewed appreciation for traditional and modern dance forms, reinvigorating its practice and significance.

All of these milestones in hula’s journey highlight its resilience and significance as a beautiful art form and a sacred custom treasured by the Hawaiian people.

Read more: What Is Maxixe Dance?

Hula Kahiko – Traditional Hula

Now that the history of the hula has been talked about in depth. Let’s get down to the basics and explore the two main types of hula.

First, you have the hula kahiko, the ancient or “traditional” hula. This term is broadly used to refer to all kinds of hula dance before 1894. It is characterized by the lack of modern instruments (guitars, ukuleles, etc.)

Most hula dances of this kind are religious and dedicated to honoring Hawaiian gods and goddesses.

Precision was crucial, as even a minor mistake was seen as invalidating the performance and could bring bad luck or dire consequences.

It encompasses diverse styles, from solemn and sacred to lighthearted.

Dancers wear traditional costumes. The performance usually has an austere aesthetics choreographed to have a deep reverence for its spiritual origins.

Attires

In traditional hula, female dancers were adorned with the pāʻū, a wrapped skirt, while being topless. However, the attire has been modified over time.

To showcase opulence, the pāʻū would be much longer than the standard tapa length, which is only wrapped around the waist.

Visitors could see dancers draped in multiple yards of tapa, significantly expanding their circumference.

Dancers also embellished themselves with necklaces, bracelets, anklets, and various lei, including headpieces (lei poʻo), bracelets, and anklets (kupeʻe), along with other hula dance accessories.

Additionally, a skirt made of green kī (Cordyline fruticosa) leaves could be worn on top of the pāʻū, arranged in a dense layer of around fifty leaves.

Kī leaves held sacred significance for the goddess Laka, and the hula dance.

Only kahuna (experts) and aliʻi (nobility) were permitted to wear kī leaf leis (lei lāʻī) during religious rituals.

Similar leaf skirts made of C. fruticosa leaves, known as sisi, are used in sacred dances in Tonga. They typically incorporate red and yellow leaves.

Conversely, male dancers wore the malo, a loincloth, as their everyday attire.

Like their female counterparts, they could wear bulky malo made from multiple yards of tapa. Male dancers adorned themselves with necklaces, bracelets, anklets, and lei.

The lei and tapa used in performances were gathered from the forest after offering prayers to Laka and the forest gods.

These items held a sacred essence, and it was customary not to wear them again after the performance.

Lei were often left on the small altar dedicated to Laka, which could be found in every hālau (hula school), serving as offerings.

Chants (Oli)

The language held a spiritual power in Hawaiian culture known as mana, especially when delivered through oli (chant).

Skilled composers and chanters were highly respected for their mastery of language manipulation. Chants played a vital role in various aspects of Hawaiian society, serving social, political, and economic functions.

Traditional chants were diverse in context and purpose, with specific types dedicated to prayer, ritual dance, cosmogeny, genealogy, birth, name, lamentation, games, love, and expression.

Oli could be performed with or without dance (hula), while mele encompassed a broader definition, including poetry and linguistic composition.

The vocal style of a chant depended on the combination of its general style and performance context.

Different techniques, such as kepakepa, kāwele, olioli, ho’āeae, ho’ouēuē, and ‘aiha’a, distinguished the vocal quality and character of each style.

Within hālau hula (schools), the request for permission to enter and learn from the kumu (teacher) is important for students.

Oli, such as the oli kāhea “Kūnihi,” is often used in this context, with students chanting outside the entrance until granted permission by the kumu.

Oli is considered the most typical form of indigenous music that lacks metered structure. Different vocal techniques, such as kepakepa, kawele, olioli, ho’āeae, and ho’ouweuwe, were developed to adapt to various performance circumstances.

The mastery of vocal techniques and the seamless integration of poetic text into oli style are touchstones for good performers.

Instruments and Implements

A performance of hula kahiko is typically done with the backing of a live band playing a variety of traditional instruments, such as:

- Ipu: a single gourd drum.

- Ipu heke: a double gourd drum.

- Pahu: a drum covered in shark skin.

- Puniu: a small knee drum made of a coconut shell, covered in fish skin.

- ʻIliʻili: castanets made from lava rocks.

- ʻUlīʻulī: gourd rattles.

- Pūʻili: split bamboo sticks.

- Kālaʻau: rhythm sticks.

Performances

So, when is the hula dance performed?

Informal hula performances for everyday enjoyment or family gatherings are casual affairs.

However, when hula is performed as entertainment for chiefs, it becomes a significant event. Chiefs would travel within their territories, and each locality has to accommodate and entertain them.

Hula performances serve as an act of loyalty and often flattery towards the chief.

Typically, male dancers would start the performance, followed by female dancers who would bring it to a close.

Kahiko performances would commence with an opening dance called “kaʻi” and conclude with a closing dance called “hoʻi” to signify the presence of the hula.

Various hula was dedicated to celebrating the chief’s lineage, name, and even his intimate parts.

Sacred hula dedicated to Hawaiian deities were also performed. And all these dances had to be executed flawlessly to avoid any misfortune or disrespect.

Hula ‘Auana – Modern Hula

The Hula ‘auana – also known as the modern hula – is a fusion between the traditional hula dance and Western music and instruments.

The core of the hula dance is still there, including the storytelling aspect, which includes stories that happen after the 1800s.

However, the costumes of the dancer and the music are all different. Dancers wear more revealing and modern clothes. The music sees the incorporation of Western instruments like guitars.

Attires

The traditional hula dance attire consisted of kapa cloth skirts for women and a simple loincloth (malo) for men.

However, in the 1880s, there were changes to the hula costume, with grass skirts becoming more prevalent.

The attire chosen by hula instructors reflects their interpretation of the mele (song).

Each piece of the ‘auana costume, from the clothing color to the type of adornments worn, symbolizes an element of the mele, such as a significant place or flower.

While there is some flexibility in choice, most hālau (hula schools) adhere to accepted costuming traditions. For example, women typically wear skirts or dresses, while men may wear pants, skirts, or a malo.

Formal clothing like muʻumuʻu for women or a sash for men is worn for slower and more graceful dances. In contrast, faster and livelier dances are performed in more revealing or festive attire.

Songs (Mele)

Hula ʻauana mele, or songs, are typically performed in a manner resembling popular music. You’ll hear a lead voice singing a major scale, occasionally accompanied by harmonies.

The subject matter of these songs is diverse, covering a wide range of human experiences. They can be written to pay tribute to important individuals, places, or events or express emotions and ideas.

In Hawaiian music, the distinction between hua kahiko (ancient hula) and hula ʻauana is defined by the dance style and the accompanying sound.

Poetic lyrics have always been a fundamental artistic element in traditional Hawaiian music. As such, early Hawaiian artists didn’t focus on instrumental music but used nose-blown flutes with limited notes.

However, when Hawaiian culture encountered Western music, musicians began incorporating various instrumental techniques into the traditional repertoire.

The sound becomes broader and more dynamic in hula ‘auana performances.

Instruments and Implements

Besides traditional instruments (already described above), you may also find steel-string guitars and basses making an appearance in a hula ‘auana ensemble.

Performances

Hula ‘auana performances are typically given at festivals, cultural fairs, and private concerts.

Because they have a more approachable format via their use of Western music and styling, they typically enjoy more attention from tourists.

Hula Dance Moves

Wondering how to do the hula dance?

Hula is a very complex dance that’s only ever done by professionally-trained musicians and artists.

There are full-fledged schools (hālau) devoted to teaching this art.

Nevertheless, there are a couple of basic moves, mostly consisting of arm movements. Most people can pick up with a little bit of practice:

- Ha’a: Dancers stand erect with their knees bent in a basic stance.

- Lewa: The hips are lifted in this step.

- Hela: The dancer touches one foot to the side at a 45-degree angle in front of their body while keeping the weight on the other foot, then returns the foot to the starting position and repeats with the other foot.

- Ka’i: One foot is lifted, and the heel of the opposite foot is raised and lowered. The movement is then repeated with the other foot.

- ‘Ami: A basic hip rotation with variations such as ‘Ami ‘ami, ‘Ami ‘ôniu, and ‘Ami ku’upau.

- Holo: Similar to lewa, it appears as a running movement.

- Kâholo: The dancer performs the lewa move while traveling. They step to one side, follow with the opposite foot, then step to the same side again.

- ‘Uehe: The dancer lifts one foot, shifts their weight to the opposite hip when stepping down, and raises both heels to push the knees forward. These movements repeat on the opposite side.

- Lele: In this walking move, the dancer lifts their heel with each step.

Hula Dance For Kids At Schools

As we said earlier, there are serious schools devoted to teaching people how to dance the hula. These schools – called hālau – are headed by teachers known as kumu hula.

In many hula schools, a hierarchical structure starts with the kumu as the teacher, followed by the alaka’i as the leader, kōkua as helpers, and finally the ‘ōlapa or haumana as the dancers or students.

While this hierarchy may not be present in every hālau, it is common.

When entering a hula practice space, most hālau perform a permission chant as a collective before awaiting the response of the kumu with their entrance chant.

Once the kumu finishes, the students are granted permission to enter. One frequently used entrance or permission chant is “Kūnihi Ka Mauna/Tūnihi Ta Mauna.”

Famous Hula Dancers

Over the decades, many famous hula dancers have made it big in Hawaiian islands and the US and worldwide.

Beverly Noa

Beverly Kauiokanahele Noa (June 14, 1933 – October 19, 2017) was one of the most famous Hawaiian hula dancers to ever live.

Beverly was born in Los Angeles, but she was raised in Honolulu.

At the tender age of six, she began studying the hula under the tutelage of Louise Beamer and later with ʻIolani Luahine.

In 1952, Noa was crowned Miss Hawaii and became a top ten finalist in the Miss America contest the following year.

Beverly took the opportunity to perform the hula at prestigious venues such as the Tapa Room and Royal Hawaiian Hotel, captivating audiences with her graceful performances.

Noa’s artistry and captivating presence elevated hula dancing to new levels. So much so that she was inducted into the Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame in 2014 and received the I Ola Mau Ka Hula Award in 2017.

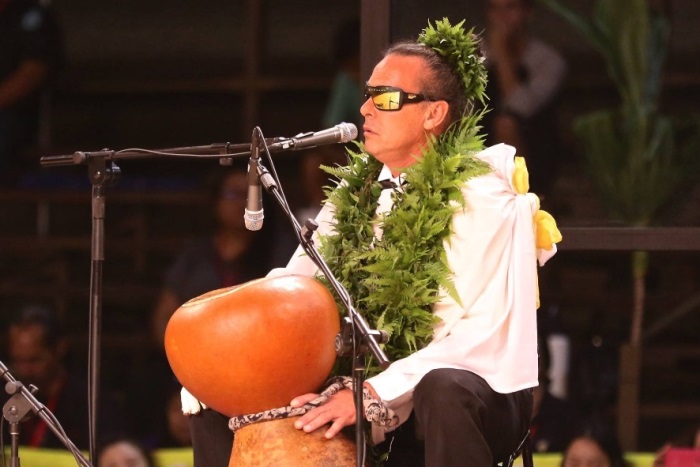

Mark Keali’i Ho’omalu

Mark Keali’i Ho’omalu is a musician best known for his work in the beloved Disney movie “Lilo and Stitch,” including the iconic songs “He Mele No Lilo” and “Hawaiian Roller Coaster.”

With numerous accolades to his name, including the prestigious 2015 Outstanding Achievement in Performance, Ho’omalu’s influence extends to Hawaiian dancers, singers, and artists across the US.

Final Words

And that’s the basics that you need to know about the hula dance. But do note that it’s not all that you can know.

If you want to dive deeper, you’ll need to hear the stories told by performers and kumu hula themselves, which may not be written down anywhere.

Such is the depth and richness of the hula dance history!

What’s your favorite part about the hula? Tell us in the comments!